Intelligent irrigation

Why Walter Schmidt became an IoT pioneer instead of retiring

Walter Schmidt entered the world of sensor-based irrigation systems at the age of 64. He has developed his technology even further since then – in part thanks to IoT. Networking the grass on the pitch of FC Basel’s stadium was just one of his many projects.

Text: Tanja Kammermann, Images

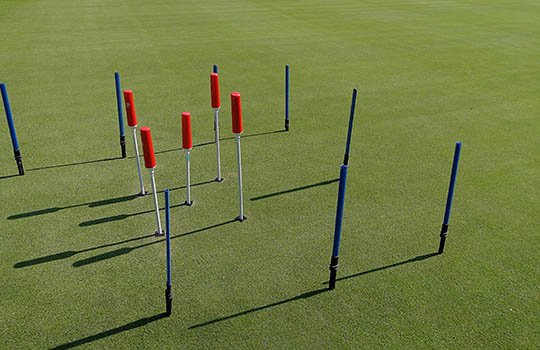

We pass through a narrow wooden staircase, go past a potted plant containing some sort of technical device, and find ourselves amongst a variety of red poles, some short and others about as tall as a man, are standing and lying all over. To the left is a door marked “Laboratory”. “I don’t let anybody else in there,” Walter Schmidt says in response to my questioning look. Instead, he takes us to his offices, which are housed in an old school building in the hamlet of Russikon. He painted all the pictures adorning the walls himself, he tells me with pride. This is where Walter Schmidt has spent the past 14 years working on developing the perfect irrigation system and experimenting with the Internet of Things.

He developed his very first irrigation sensor in 2004 in his own goldsmith’s studio. Back then, his son-in-law, a gardener, had challenged him to develop an intelligent irrigation solution for him instead of retiring, because there was no such thing on the market. “I couldn’t let that challenge go unanswered. I spent a whole afternoon going through all the laws of physics that might somehow be relevant and finally found a solution. I didn’t think an idea that crazy could work.” Indeed, the first prototype he pieced together didn’t. But three weeks later, he was able to measure when his wife’s potted plant was about to die. “I’m a trained physicist and was clueless about plants.”

Walter Schmidt, 74, is the think tank behind Plantcare.

Today’s solution still consists of a specially developed felt material inserted into the soil which serves as an interface between the soil and the sensor. Moisture is measured by heating the sensor briefly and then determining how long it takes to cool down, which changes depending on the soil’s moisture level. The amount of time it takes for the sensor to cool down is therefore a reliable indicator of the soil’s water content. The measurements are transmitted to a controller at regular intervals via the Internet of Things. Schmidt patented this simple yet revolutionary system. It works so well, in fact, that garden tool manufacturer Gardena purchased a licence for it in 2005 and still sells this system today. His retirement was postponed indefinitely with the founding of his company, Plantcare.

Half-hearted solutions and burnt fingers

Walter Schmidt developed an adapted sensor on the same technical foundation in 2007. He focused on indoor plants to prevent his latest innovation from negatively impacting the Gardena licence. They went into business with Luwasa in Allmendingen, built a protype and sold 100,000 units. “At some point, we were just handling the logistics. It was tedious. And in the end, the things were being sold at Obi. That’s a dirty business.” The question eventually arose whether to have the sensors produced in China or whether to stop. Another chapter had ended, but the technology wouldn’t release its hold on Schmidt.

The weatherproof housing conceals high-quality electronics: soil moisture sensors from Plantcare.

In 2009, Walter Schmidt’s laboratory produced the Plantomat, a technologically advanced product that was yet another marketing flop. “We just couldn’t gain a toehold in the market. But I kept on trying, I didn’t quit. Sometimes I have to start with half a solution, burn my fingers, and learn a lesson from that experience.”

Help for farmers

Walter Schmidt’s determination soon paid off. He focused on developing the system for more complex installations in the agricultural sector – for crops including tomatoes or berries. “We initially only used our system for taking measurements, not for irrigation control systems. But farmers really just want to know when they have to water their crops. They’re not interested in soil moisture content.” A survey among farmers brought several insights: The system must be robust and practical, have a long service life, be quick to use and contain cheap, easily replaceable batteries. An IoT sensor with considerably more wireless performance was needed, one capable of covering a distance of 20 kilometres.

The next logical step happened in 2011 when Schmidt and his team developed an irrigation control system and a self-learning algorithm. “That means crops are watered more if there’s a north easterly wind blowing or it’s extremely hot. Soil moisture levels around the root are kept within an adjustable range; the system notices if it’s irrigated too much and automatically readjusts.” Plantcare solutions are a big investment for farmers and a single sensor comes with a price tag of around CHF 600. Data is displayed directly via the servers in a specially-developed dashboard. In the meantime, Plantcare mainly earns its money through the sale of hardware and services. Worldwide, there are more than 250,000 soil moisture sensors in use on every continent.

Driven by his ideas

“Soon, our sensors will let us simultaneously measure air humidity and temperature to detect fungal infestations on the plant at an early stage.” Walter Schmidt holds six patents for his irrigation solutions and spent a total of CHF 700,000 on them. He also just recently filed an application for his seventh patent: “We want to be able to measure soil fertiliser content someday.” Being a foresighted person, Walter Schmidt has added three more standard interfaces to the soil moisture slot which offer space to attach any other kind of sensor.

The first soil moisture sensor and its enhancements were all created in this old school building.

Walter Schmidt has always been an innovator and was lucky enough to be surrounded by people who were finally able to implement his projects. “I have a backpack of skills to play around with. They give birth to something new every now and then, but I can’t force it. I’ve also had the good fortune to have been associated with the Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft for 20 years, a collaboration that has put a large network at my disposal. I always ask around: Do you know any experts on this?”

He has to build his own international network

His sensors have been transmitting data over the LoRaWAN standard since 2016. “We have to provide the gateways for the networks ourselves for our projects in Austria and Germany. Initially, that’s also how it was in Switzerland. We’ve been working with Swisscom’s LoRaWAN-based Low Power Network (LPN) for a while, now, and that makes us extremely happy.”

At the start of the new year, a successor will be taking over the management of Plantcare. “But I want to stay in charge of R&D. My work is extremely fascinating, I have so many social interactions and it’s all so successful. I can’t just hand a baby like that over to somebody new.” What about retirement? “Too boring,” says Walter Schmidt.

The five most important IoT projects

Personal details

Walter Schmidt was born in Styria, Austria, in 1944. He studied mechanical engineering and physics at the Graz University of Technology. From 1979 to 1991, he headed up the Electrical Connectivity division of Oerlikon Contraves AG in Zurich. From 1991 to 2001, he was co-owner and CEO of Dyconex, a high-tech electronics company. After that company was sold, he became a Business Angel for various start-ups.

Walter Schmidt is the founder of the European Interconnect Technology Initiative and president of the “Crazy Guys”, a group of specialists from the industrial and scientific field of electrical connectivity. He holds over 80 patents and lives with his wife in Russikon.

More on the topic